Fraud Proof in OP Stack

Why Fraud Proof is Needed

In OP Rollup, anyone is allowed to submit blocks without providing proof of validity, making the system more flexible and efficient. However, how can the validity of blocks be ensured? The OP Stack-based chain specifies a time window and sets a challenge period. During this period, if a verifier detects a discrepancy between the updated state on L1 and the state after processing the data provided by DA, a fraud proof is initiated to receive substantial rewards. The simplest way for L1 in such a case is to re-execute the transactions on L1 smart contracts and check if the state is correct. This method is known as "simple replay proof."

Classification of Fraud Proof

Fraud Proof is an adversarial protocol, and based on the number and nature of interactions during the proof process, it can be categorized into several types.

Non-Interactive Fraud Proof

The core idea of non-interactive fraud proof is to re-execute transactions to confirm the consistency of the results. An EVM environment in L1 is used to implement an EVM environment by Solidity, accepting any type of smart contract in EVM opcode format (EVM in EVM). However, this design has some limitations, such as:

- Assertion Size Limitation: Due to gas constraints, there is a limitation on the size of assertions. If the assertion is too large, it may not execute through the EVM, leading to an inability to validate state changes.

- Verification of L2 Transactions on L1: To support L2 transactions running on L1 and verify L2 state changes, a series of contracts may need deployment on L1, and processing of compiled opcode may be required. This increases system complexity and gas consumption.

- Increased Gas Consumption: Function calls consume more gas than a single opcode. EVM in EVM operations may lead to significant gas consumption. This means that it is not possible to fully simulate the execution of an entire L1 transaction, only a small portion of opcodes can be executed.

- Increased Complexity: The design of EVM in EVM introduces additional complexity, including handling of compiled opcode after contract compilation. This increases the difficulty of system maintenance and understanding.

Interactive Fraud Proof

Considering the challenges posed by non-interactive fraud proof, the interactive fraud proof approach appears to be more favorable. Unlike the transaction re-execution in non-interactive fraud proof, interactive fraud proof can focus more on the disputed portions between the parties, reducing the data processed on the chain. An example of this is a multi-round interactive proof, a protocol involving back-and-forth interactions between a challenger and a sequencer. For a disputed block, binary search / bisection can be used to identify the problematic instruction, minimizing the work that L1 must complete during a dispute process. L1 no longer needs to replay the entire transaction, only re-executing a specific instruction is necessary.

Comparison of Interactive and Non-Interactive Fraud Proof

| Aspect | Interactive Fraud Proof | Non-Interactive Fraud Proof |

|---|---|---|

| Time Efficiency | Time is extended, high requirements for short-term on-chain interactions, limited by interaction efficiency | Verification time is relatively stable compared to interactive fraud proof |

| Client Modification | Requires minimal modifications to the client | Requires significant modifications to the client to support L1's simulation of L2 operations |

| L1 Contract Adaptation | Not affected, can directly use L1 contracts on L2 | Cannot directly use L1 contracts on L2, requires adaptation |

| Space Efficiency | Does not need to publish status declarations for all L2 tx, only submits problematic opcodes | Needs to publish status declarations for all L2 tx, occupying significant L1 space |

| Gas Limitation | Interactive FP only submits problematic opcodes, smaller Gas limitation | Non-interactive FP submits all tx, larger Gas limitation, affecting L2 tx execution |

| Instruction Limitation | No instruction limitation, can submit any opcode | Subject to EVM limitations, cannot use instructions not present in EVM |

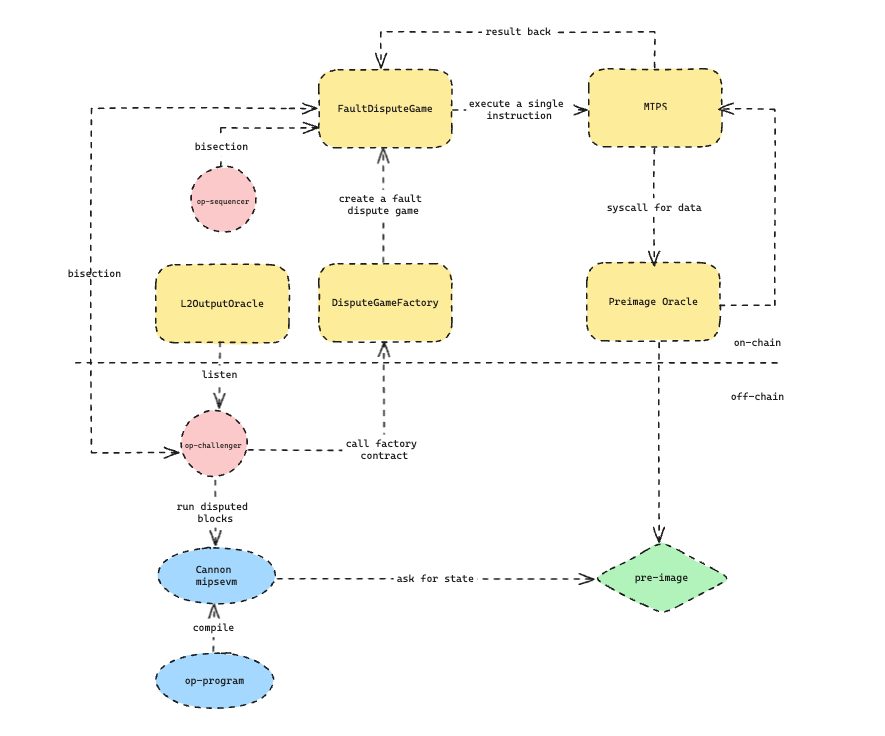

Design of Optimism Fraud Proof

Optimism has designed its Fraud Proof system with high decoupling and abstraction of components, making components replaceable.

Core Components

Optimism's Fraud Proof system has three core components:

Fraud Proof Program

Fraud Proof Program (FPP) is designed as a Client-Server architecture system. It initiates the fraud proof process by accepting commitments for all Rollup inputs (L1 data) and handling disputes.

As a stateless (deterministic, the same input yields the same output) middleware, it verifies claims about L2 state transitions. It applies L1 data to the finalized L2 state, reconstructs the latest L2 state, fetches data through the Preimage Oracle, and completes state changes in memory. This process involves two steps:

- In

op-node, processes L1 blocks into L2 block bodies. - In

op-geth, reconstructs L2 state from L2 block bodies.

FPP consists of two components:

op-program-client(opens in a new tab): Responsible for receiving parameters of Layer 2 blocks, compiling them into MIPS instructions, and loading them into the Cannon MIPS simulator to provide the initial state for disputes.op-program-host(opens in a new tab): Functions as the server environment for op-program-client, providing the necessary basic data for op-program-client to replay blocks.

Fraud Proof Virtual Machine (FPVM)

Implements the functionality of a state transition function, providing external data for the state transition stage through a pre-image oracle and initiating fraud proofs through op-program.

Supports various implementations, such as Cannon (based on the MIPS instruction set) and Asterisc (based on the RISC V instruction set).

Dispute Game

Determines whether the L2 state is correct by binary searching through the instruction trace given by an FPP running in a simulator. Ultimately, disputed blocks are reduced to a single instruction, resolved through the VM. It is essentially a simple state machine, initializing a RootClaim (True or False) for any information.

Preimage

In addition to these three components, there is also a Pre-Image component. The Pre-Image Oracle serves as the communication method between FPP and FPVM. A pre-image corresponds to the raw data for a specific hash. By deploying relevant preimage oracle contracts on L1, L1 can use preimage to access L2 state based on a hash.

The request type for pre-image is determined by its first byte, for detailed information, see here (opens in a new tab).

Workflow of Fraud Proof

- The op-challenger monitors the

L2OutputOraclecontract, periodically checks the legality of blocks, and initiates a challenge as soon as an illegal block is detected. - In the off-chain environment, op-program is compiled into the MIPS instruction set (mipsevm). Then, based on block information, a corresponding instruction trace is generated (L1 block -> L2 blocks -> L2 state). Some status information is also callback to op-challenger.

- The op-challenger creates a

FaultDisputeGamecontract through a factory contract. Based on the input from the instruction trace, it uses binary search to determine the ultimately disputed single instruction. - Using the pre-state of this instruction (from the

Preimage Oraclecontract), the instruction is executed in the MIPS contract, completing the state transition and obtaining the post-state. - The state is returned to the

FaultDisputeGamecontract, determining the correctness of the instruction and completing the fault proof.

Sign up for our newsletter

Stay up to date with the roadmap progress, announcements and exclusive discounts feel free to sign up with your email.

© By Whisker —@whisker17